Je t’épaule tu me respires

avec: Anne Bourse, Elise Carron,

François Lancien-Guilberteau, Liz Magor,

Jean-Charles de Quillacq, Gino Sarfatti,

Natsuko Uchino

8.02 - 31.03.2018

opening Thursday, February 8, 6-9 pm

cur. Marcelle Alix, Franck Balland and Aurélien Mole

We wish to hear what works want and make sure that this exhibition’s visitors can also be attentive to it, even if it is difficult to be guided yourself between this desire to touch that attracts or questions us and the often unstable position of the spectator used to keeping a certain distance, verified by a scenography as explicit as the glances of the guards. If its presentation pushes the work to conceal itself, how can the visitor meet its reality, its movement, its formal genealogy, its present life and the time that unites us? “Please touch” we could read in the 1960s, for works today that are all the more untouchable in that their presentation itself does not permit the tranquil admission of an enviable form of vulnerability. We have always stressed the advantage of designing exhibitions in a space similar to that of the apartment in which the relationship to the works is more relaxed. Each artist adds here to this idea of living with the works whose image is less important than the sensation of perceiving a strong presence and existence, to which we react in many different ways.

CB: As far back as I can remember, this ethic of "taking care" that the exhibition puts into practice, was shown when I attempted to build a relationship full of energy and movement when facing artworks. My first idea was to orient myself to the conservation and restoration of pictures. I wanted to act vis-à-vis a work that was itself acting. The most important thing seemed to me the responsible attitude that I could have in protecting artworks that could be destroyed in many ways, often by a lack of understanding. With time, other professions that made it possible to touch the works appeared to me to call on a love that was both extraordinary and obvious. This exhibition is less a collective curatorship than the assertion of our respective positions vis-à-vis forms that we look at and handle every day, not only to exhibit them. If there is protection, there is also a less theoretical, sometimes more physical relationship that has us side, in a certain way, with what the objects want. How can we distance ourselves from the exhibition to let ourselves be influenced by the work? I imagine that we will do so through an amorous dialogue, the very one that Chris Marker and Alain Resnais defended in the film Statues Also Die (1963). The work is our equal, whether it precedes us or survives us, its time is limited and its weakness is the most wonderful sign or the best of mirrors, I believe, to solve our problems as spectators.

IA: It is obvious to us that we focus on this question of care, which in fact, is closely akin to a form of ethics or even a political choice in the relationship that it implies with the works but also between human beings. It does not concern making this question into a theme but more of turning it into a collective and generous energy that acts in the gallery’s space, from the offices to the nearby bar where we organize the opening drink. I like to think that our relationship with the works and with people are of the same nature, that the works act on us like people, at various moments in their own lives. It is for this reason that the presence of Liz Magor at the exhibition with two new pieces created from recycled blankets, mended and preserved in plastic film was a necessity. Using a principle already present in her work, she pushes to the extreme the care given to these woolens riddled with holes and stains by minutely examining each of the accidents, incorporating them into a composition of a pictorial nature. In observing her installing the works in the same ways as we might welcome friends in a new place, this horizontal and affective relationship with the work seemed essential to us. We have already brought up in several texts our taste for a non-dual thinking, of a holistic nature, which makes it possible to rethink our relationship with the inanimate beyond a human/nonhuman, subject/object hierarchy. This is what creates, I believe, the vulnerability, the precariousness and the not very definitive character of what constitutes this exhibition.

AM: The fact that it is not a question of a theme but of an ethic seems important to me. The staging of "taking care" is much too demonstrative, whereas, fundamentally, it should be incorporated into our relationships with artists, works and the other to such a great degree that it become indiscernible from them. At the core of this inclination to taking care, there is the idea of attention that seems to be, from my viewpoint, the most important attitude to take. Attention is both the starting point for everything that will follow but also a result: that of an opening to the world. In Gino Sarfatti’s practice, the idea of a lamp is usually based on the form of a light bulb or neon light. Starting from an industrial object, perfectly functional but directed at no one in particular, for Gino it is a question of thinking of forms able to welcome and enhance the formal and luminous characters of light bulbs that subsequently become inseparable from the lamps that were thought of for them. These lamps are interfaces between the factory and the home. They direct standardized light bulbs to specific activities such as reading, a dinner with friends, an evening gathering. Trying to favor attention conditions is also increasing the impact that an artwork can have on our life. This can be a hanging on a line such as the one thought of by John Dewey and Albert C. Barnes for the latter’s collection, this can be a signed mediation text, this can be that trip that we take to specifically go and see a given artwork whether it is Matthias Grünewald’s retable or Frank Lloyd Wright’s house on a waterfall… Attention is the moment when we merge into the initial destination of the work desired by the artist (whether we imagine it or not). At the heart of François Lancien-Guilberteau’s practice there is a form of specific attention. In his images, for example, the relationship to the model, the way of preparing her, counts as much as the moment when she is captured. It is as though the entire sentimental investment was oriented toward this area outside the scope of the image. Consequently, sharpening and applying makeup are two actions that precede those of cutting and appearing. The makeup removal powder comprised of dried bird droppings used to remove the toxic lead white of the geisha’s face, has such a specific tint that it shows the skin under the makeup.

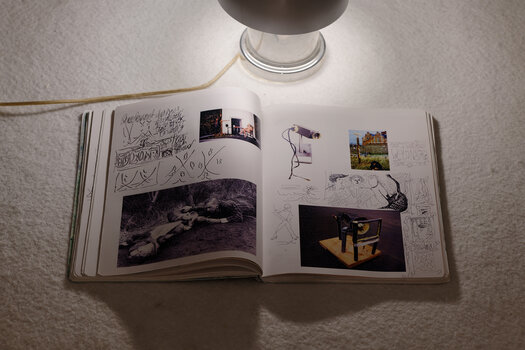

FB: I also feel that it is necessary to stress that this exhibition was created like a series of invitations that do not solely link a certain number of objects to each other, but more following the flow of intuitions and desires. Among them, there is obviously this idea of destination that Aurélien talks about. In Anne Bourse, the work finds its place where a relationship already exists: on a towel with geometric motifs belonging to her father or in a catalogue of Jimmie Durham, whose pages had been gradually blacked out, then increased with comments and drawings. It is not so much a gesture of appropriation but the continuation of a dense and silent conversation, stretched out over time, whose terms recount the intimacy that was established with the object and the entire imagination that it contains. The swirling, almost invasive forms, that characterize her line, express the continuous movement of a personal language born out of the quest for the other. There is nothing iconoclastic however in these lines that resemble “scribblings,” and like the works of Jean-Charles de Quillacq with which these objects fraternize in the gallery’s basement, they speak to us of an incessant link with a desirable material. The care that Jean-Charles’ pieces expect from us is more ambiguous: oozing and erectile, unwilling to quietly occupy their role as art objects, they attempt to subject us to their own needs, without our really knowing if they wish to be relieved, excited or ignored. For Anne, as for Jean-Charles, something fundamental is being played out in the need to reduce the distances with the works: they then act as intermediaries that are both humble and powerful permitting an active relationship with those who look at them to be maintained.

IA: A gallery is generally envisaged as the neutral space intended to welcome the expression of a desire toward fetishized art objects, in order to favor their acquisition. Our desire with this exhibition is, I believe, to make the multi-directionality of the desires that are at work in it obvious: not simply that of the potential collector toward the object, but also the capacity of desire of the objects themselves, the desire of the artists toward their objects and those of others, and our desire to be together. The challenge for me is to make our personal inclinations ever more visible, to make the gallery a place that is more incarnated than the neutral showcase designed in the sole goal of encouraging the desire for acquisition. The invitation extended to Elise Carron to participate in the day of the opening through a “potluck buffet” is linked to Barbara Quintin’s arrival at the gallery in November and their recent collaborations at Le Quadrilatère in Beauvais and at La Panacée in Montpellier. In the same way as for Natsuko Uchino, with whom Elise had already worked on a shared creation, artistic work consists here in blurring the lines between the utilitarian object, the artwork, the performance accessory, the exhibition and its traditional opening event. It is not a question of “activating” works but rather of imagining that all the objects can be laden with the same desire and that we cannot do anything other than use them as carpet, table, tablecloth, carafe, garment. Natsuko once again directs in her proposals on the ground floor an energy linked to actions that her ceramics and sequoia pieces never abandon. The artists’ life styles will have permitted us to go beyond simple discussions to penetrate the material and let it speak in its turn.

Anne Bourse born 1982, lives in Paris.

Elise Carron born 1988, lives in Paris.

François Lancien-Guilberteau born 1985, lives in Paris.

Liz Magor born 1948, currently lives in Berlin, on a DAAD residency.

Jean-Charles de Quillacq born 1979, lives in Paris and Sussac.

Gino Sarfatti, born 1912, died 1985.

Natsuko Uchino born 1983, lives in Saint-Quentin-la-Poterie.

Special thanks: Juliette Hage, Michel Rein, Arnauld and Françoise de L’Epine, Camille Allemand and Charlotte Alves, Jacques and Chantal Grandjean, Samir (Le Pataquès bar), Astier-Villatte, Galerie Jousse and Galerie Eric Dupont.